In the current world context, we may feel under more pressure. Dealing with so much new information daily and having to change behaviours and navigate this change at such a fast pace can be exhausting. Some days you feel like you are riding a wild rollercoaster where the only way to get through is to hold on tight, close your eyes and ride it out.

When we are under more pressure than usual, our brains often go into autopilot and we can fall into automatic and biased thinking traps, without even recognising it. In this context of rapid change and increased perceived and actual threat, our brains tend to rush in and make more of these automatic assumptions; particularly about people we work with. These thinking traps can affect the quality of our relationships and lead to social and psychological disconnection at a time when we need connection most.

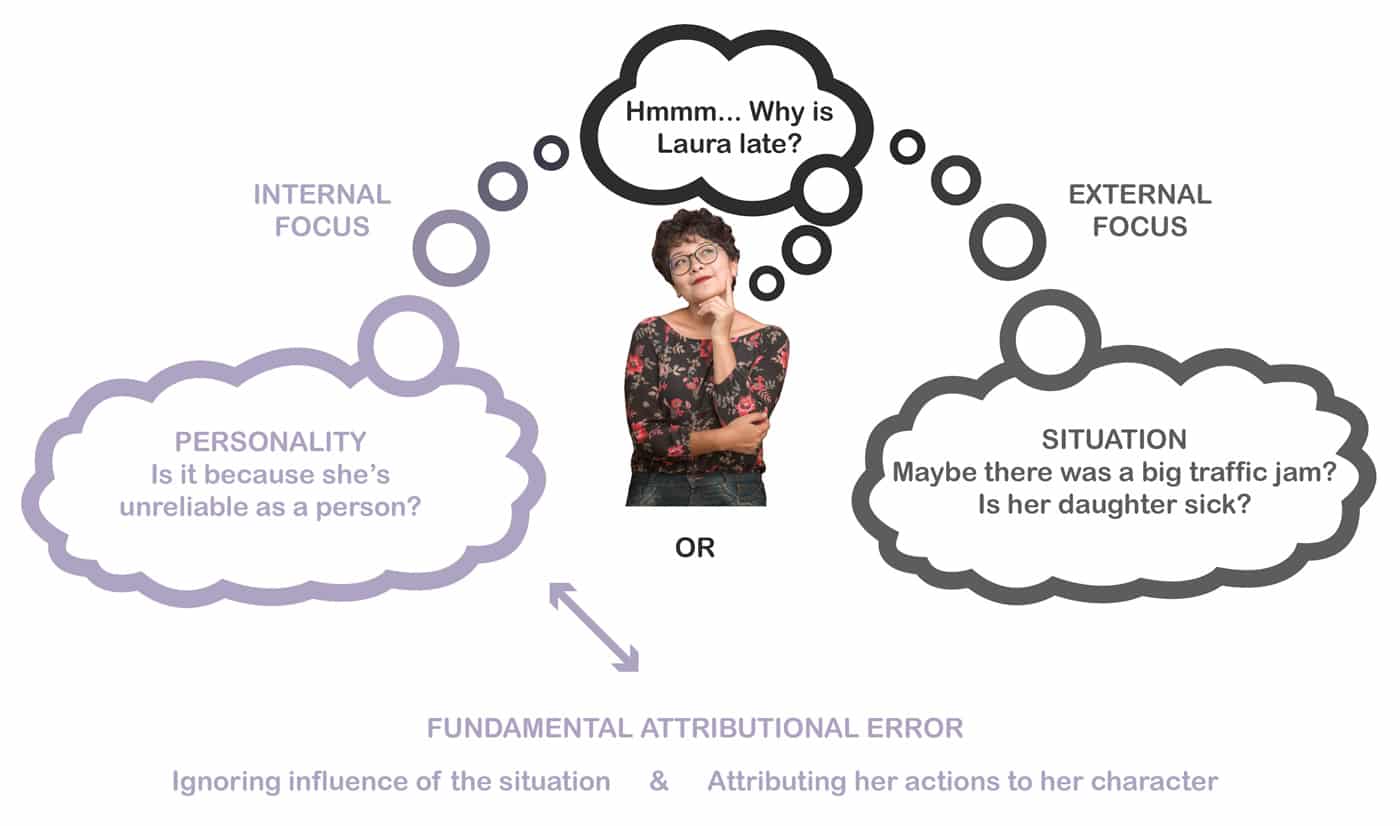

In social psychology, one such thinking trap is called the fundamental attribution error. It is the tendency for people to under-emphasise situational explanations for an individual’s observed behaviour while over-emphasising dispositional and personality-based explanations for their behaviour. So, in the case of Laura below, it means her boss is more at risk of interpreting her lateness as an internal, personality-based flaw, such as, “Maybe she’s just an unreliable person?”, rather than thinking about the possible external, situational explanations such as,“Maybe there’s been a huge traffic jam or her daughter is sick?” The fundamental attribution error thinking trap means that we’re more likely to ignore the influence of the situation and more likely to pay attention to our brain attributing Laura’s actions to her character. That means we’re more likely to disconnect from Laura as a person, instead of reconnecting with her and seeing the bigger picture.

Another example is this. You always thought Rami was a great boss, a fantastic and fair leader who has been mentoring you over the past few months. However, you walk into this meeting today and he tells the leadership team that the project you have been working so hard on together is going to have to be scrapped or drastically re-designed. You are naturally upset but how do you feel about Rami? The automatic fundamental attribution error kicks in and suddenly you are more likely to think, “He’s fake – he is just out for himself; he’s risk-averse and obviously can’t see my talent for what it is.” Or you turn it on yourself, “I am obviously a failure; he/they don’t trust me and I shouldn’t be doing this job.”

This thinking trap gets more exaggerated and likely to occur when there are strong expressed emotions involved. Imagine sitting in a meeting with your colleague, Steve, and you see him getting more and more wound up and suddenly he walks out of the room. As humans, our brains are wired to note potential threats and we are more likely to attribute his behaviour to him being “an angry/frustrated person who didn’t like what was said in the meeting”, especially if he’s been like that for a while at the office. Instead, what if we attribute his actions to external or situational factors, such as him finding out his daughter has to move home as she’s lost her job and his car still isn’t fixed from that accident he was involved in 2 weeks ago? As a colleague or leader in the workplace, depending on what lens you take, it can have a very different effect on your relationship with Steve and the whole workforce’s perception of his behaviour, now and in the future.

Another implication of the fundamental attribution error is that we may be too easy on ourselves at times of extra pressure or threat, if we are not careful. Think about all the times we explain away our behaviour as, “That’s just me” or, “I have no control over it”, rather than thinking about the situation and about what you can control, internally and externally.

So, how can we avoid this thinking trap?

The best way to avoid this error, experts say, is to

a) acknowledge our internal biases, own them as part of human behaviour but don’t get hooked in unconsciously – remember you have choice in how you react;

b) put ourselves in the shoes of others; and

c) try to envision the pressures people might have faced, before you act or respond to their behaviours.

If we can learn to “own” our internal biases, we can start to have mastery over them when we need it most. As the saying goes, “The best defence is always a good offence.” If we try and own our internal biases then they don’t own us and pop out when we least want or need them.

It’s easier said than done though, isn’t it? So, as clinical psychologists, we advise the following.

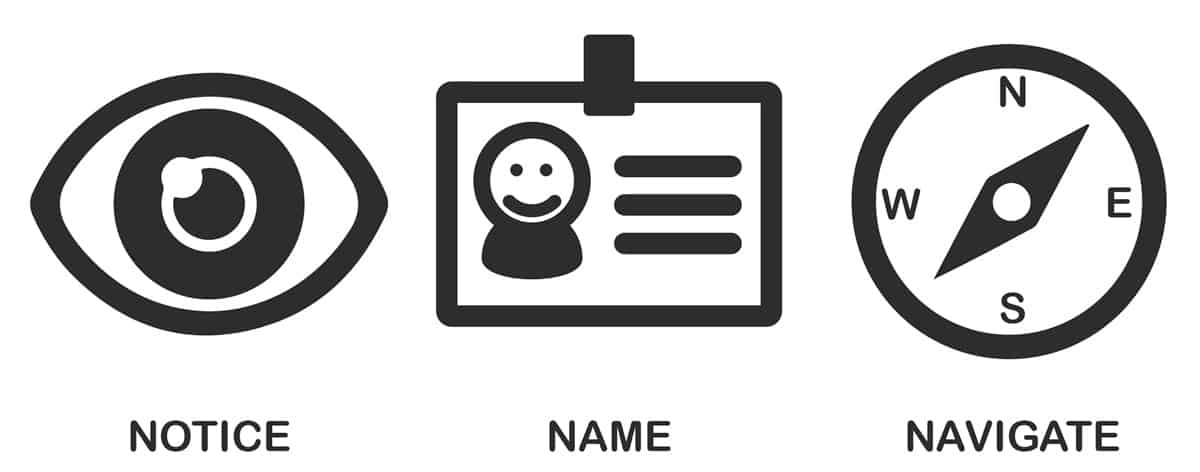

When others’ behaviours at work cause difficulties for you, try to slow down by taking a deep breath and thinking:

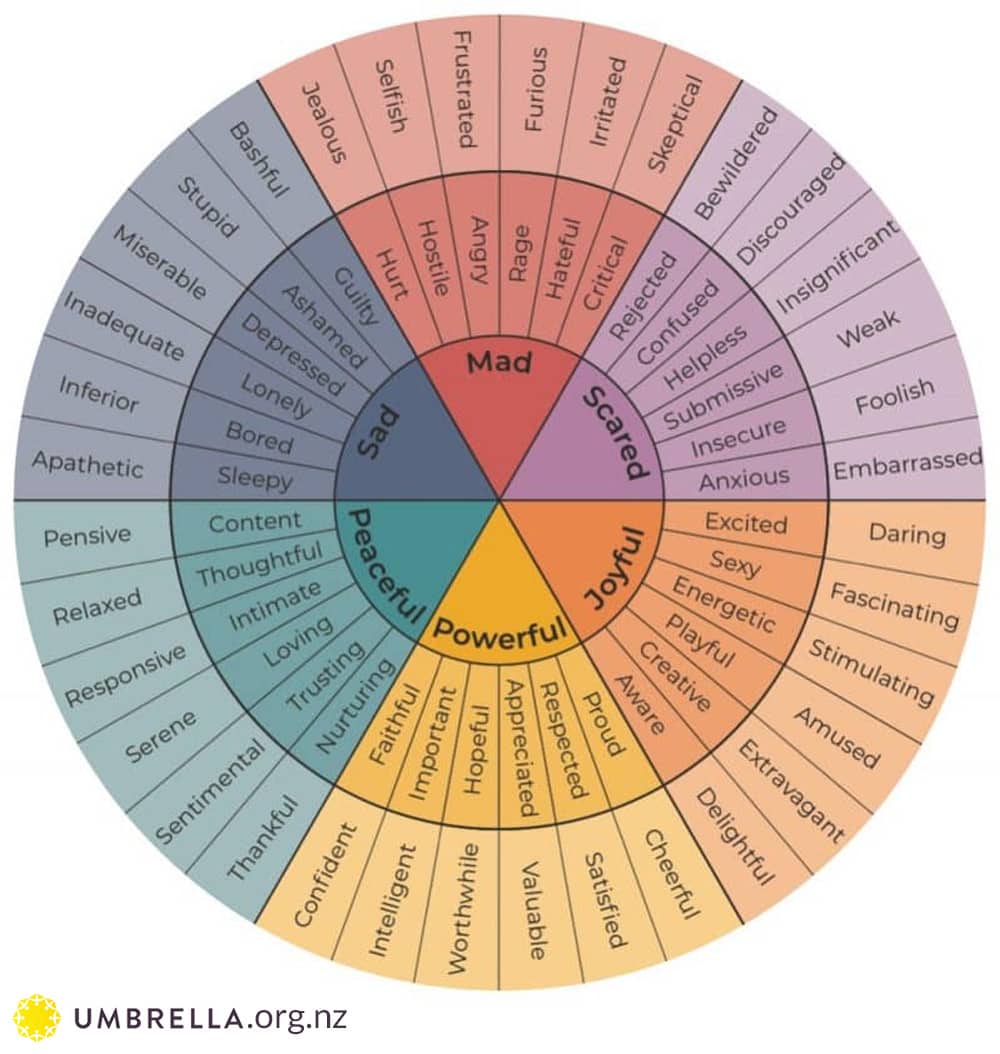

NOTICE – Firstly, bring to awareness – with compassion – the thoughts, feelings and behaviours you’re noticing. Try to avoid judgment on the process – this is just the way our brains work at times if we are under more stress but we don’t have to get unconsciously hooked in. Try to make space to acknowledge that we may be hooking into a biased thinking trap. Also, acknowledge our feelings and own them, if we can.

NAME – Try to name what you are thinking and externalise the thoughts by writing them down, without judgment. We know naming thoughts and emotions out loud or writing them down, rather than keeping them in our heads, actually helps the brain to process and file them appropriately. Then try to name the feelings this behaviour brings up in you and try to own and care for these feelings before moving on. This process not only helps our brains bring the thinking process to awareness but it also helps us not to be impulsive – it helps the brain make sense of a behaviour and brings perspective.

NAVIGATE – Try to then navigate and problem-solve next steps in a values-driven and intentional way. Think, “How can I/we approach this behaviour with compassion, perspective and with connection as its function – not disconnection?”

To manage this fundamental attribution error with colleagues, Professor of Psychology, Susan David, from Harvard Business School, suggests: “The most effective thing may be to simply consider that you really don’t know the person. When we leave room for this possibility, we open the door to continued investigation, discovery, and an evolving understanding of the people and situations we encounter in our work lives.”

This approach doesn’t mean that the other person doesn’t have to own their behaviours, or that you have to tolerate “bad” or “inappropriate” behaviours at home or work, but it does mean you’re more likely to focus on connection and partnership in solving workplace issues. Also, this approach means that you are more prepared for the rollercoaster ride at present, as you will have your eyes wide open, with intention, and can take in the full picture. From this view, you are more likely to connect to the joy and opportunities along the ride and make value-driven choices about who to take with you and when and where to jump on and jump off when you need a break.

Article Link: Susan David, Harvard Business Review 25 June 2012, The biases you don’t know you have.

Thanks to Annie for this article.