I am back from a working tour of Europe. My muscles ache, my jaw is clenched tight, shoulders are pinched and my arms feel weighted down. You might ask, “Jacqui, has this got anything to do with the exorbitant load of your luggage, which you heaved lopsided through cobbled streets and metro stations?” Well, yes, that is one explanation – I have never quite mastered the art of “less is more”.

Yet there may be another reason. What is the impact of fully uniformed military lining squares with AK47s in Paris; police walking the carriages of all moving Belgium metro trains; bag checks and body scans any time you enter a tourist destination or even a supermarket? Does the sight of militia and police calm you – or heighten your alertness to terrorism? Are my aching muscles the result of a month’s compounded tension, a consequence of experiencing Europe’s current high-risk safety status?

My past four weeks are just a slice of the reality for locals living in Europe and these thoughts mirror some of the conversations I had with Kiwis currently residing in Brussels, Berlin, Paris and London. How do we maintain resilience in the face of terrorism?

Whilst there is no universal definition of terrorism, it is helpful to begin with the etymology:

Within terrorism lies the word terror. Terror comes from the Latin terrere, which means “frighten” or “tremble.” When coupled with the French suffix isme (referencing “to practice”), it becomes akin to “practicing the trembling” or “causing the frightening.” Trembling and frightening here are synonyms for fear, panic, and anxiety—what we would naturally call terror.

At the heart of the derivation lies the “psychological warfare” of terrorism. Whilst acts of violence have an immediate impact for the people caught in the crossfire of political, religious or ideological pursuits, the perceived threat of risk reaches far and wide. As indicated in a report commissioned for NATO, “Terrorism is always intended to influence and intimidate a far larger group of people than the actual number of persons who actually become victims. It is literally aimed at striking terror in the hearts and minds of a far wider witnessing audience who identify with the victim’s plight and become fearful that they too can become the next victims”.

You can see evidence of this psychological warfare at a neuropsychological level. As a result of media, social networks and publicised recent terror attacks, our brains have been conditioned to launch our fight or flight response at the slightest trigger. The sight of solo individuals walking in public arenas holding oversized luggage, people muttering to themselves on public transport, the sound of a car backfiring.

It makes me wonder how many people are walking these cities on a knife’s edge? Fuelled by the body’s stress hormone cortisol, hyper alert and ready to be tipped into an “amygdala hijack” at any moment (our body’s evolutionary survival mechanism, commonly known as the fight or flight response). Considering our hyperactive amygdala and heightened perception of risk – how do we maintain our resilience within this reality?

Following a traumatic, shocking or significantly stressful event, it is natural for many people to experience a wide range of physical and emotional reactions. These are normal reactions to abnormal events, and can include:

- Feeling on edge

- Easily startled

- Sleep disruptions (including insomnia or nightmares)

- Flashbacks (feeling as though you are reliving the event, which can incorporate physical reactions such as sweating or a pounding heart)

- Intrusive negative thoughts (about yourself, others or the world)

- Anger, irritability, mood swings

- Avoidance of any linked reminders to the traumatic event (people, places, objects, thoughts, feelings etc.)

- Loss of interest in life activities

- Withdrawing from others

- Feelings of guilt

- Difficulty concentrating

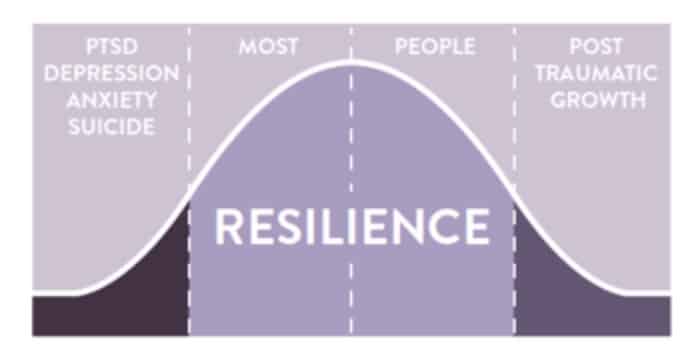

These symptoms tend to naturally fade over the following days and weeks. However, for some, these symptoms can persist (longer than a month) and significantly interfere with a person’s ability to function well in life. This is classified as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

When it comes to resilience, our aim to is protect people from developing PTSD and to enhance their ability to maintain their wellbeing (and even thrive), following a trauma. This positive recovery experience is described as Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) in psychological literature. To be more specific, PTG is “the experience of positive psychological changes that occur in the wake of a traumatic event” and usually happens in five general areas:

- Perceived improvement in relationships with others

- See new possibilities in life

- See self as stronger

- Increased appreciation of life

- Spiritual growth

People who have been able to achieve this thriving have demonstrated the ability to connect with others empathically and find meaning in the trauma.

Scientific research clearly demonstrates that our actions before, during and after a traumatic event are all important in enhancing our likelihood of PTG. I have witnessed this in my own clinical experience, and recommend people residing or travelling in high-risk cities consider the following effective actions.

Phase 1: Prevention

- Be aware of your own acute stress response patterns – would you be able to clearly identify when your body has been triggered into an amygdala hijack (fight or flight reaction)?

- Practise fast and effective strategies to calm your body – or “dial down your amygdala” – such as diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, visualisation exercises.

- Develop a detailed survival plan of how to respond to a terror attack. This plan should be practical and easy to follow, and you may need individual plans for your family / house mates/ colleagues. Just as “Stop Drop and Hold” has been drilled into New Zealanders in the event of an earthquake, well-rehearsed plans for terror attacks are no different. We want your brain to be triggered into a helpful autopilot response when you are operating in a crisis.

Phase 2: Staying calm during an event

- Draw upon your practised calming strategies

- Follow your survival plan

Phase 3: Recovery

- Practise self-care strategies (mindfulness, exercising, activities that are calming for you)

- Remain aware that your brain is unlikely to be operating at full capacity

- Take frequent recovery breaks to enable oscillation between “being on” and “recharging”

- Validate your normal reactions to this abnormal situation (“It is normal that I am feeling on edge and jittery only days after this event”)

- Maximise the benefits of “social buffering”

- Talk with your support network if it feels helpful to you (don’t feel pressured to talk, as this can be damaging rather than healing)

- Focus your conversations on how to cope and get through this difficult period

- Discuss facts and not assumptions

- Minimise your exposure to social media. Over-empathising with victims and saturating yourself with information is linked to diminished coping

- Make priority lists daily

- Maintain a calm environment around you.

Thankfully, the research highlights that many people experience traumatic incidents in their lives, but very few go on to develop PTSD. In a study of 2,953 American adults, 89.7% reported having experienced at least one seriously traumatic event (such as car crashes, health crises, crime and loss). Only 10.6% of those went on to develop PTSD (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Whilst we cannot predict when or where the next terror attack occurs, we can control our ability to install effective wellbeing strategies now and to best prepare ourselves for the unknown. As the Latin proverb “praemonitus, praemunitus” states, forewarned is forearmed. For now, if you too are noticing tension and the residual ache in your muscles, unfortunately there is no magic wand. However, what may be helpful is to start paying attention to your body’s cues: notice the tension, take deep diaphragmatic breaths to dial back your amygdala and do your best to keep living life through the lens of awareness.