How psychosocial risks lead to physical injuries: It’s not just in your head

A recent wellbeing survey (conducted by MATES in Construction) assessed more than 3,300 workers across construction, infrastructure and manufacturing in New Zealand. Nearly half of the workers reported pain, illness or disability. This is more than double the usual rates experienced by New Zealand adults.

The key drivers? Stress and mental strain, along with years of physical wear-and-tear. While construction, infrastructure and manufacturing are industries that have honed in on important physical health and safety matters, these workers identified that stress and mental strain are also playing key roles in back problems, fatigue and increased risk of injury.

Many also described how high workloads, tight deadlines and low psychological safety don’t just affect how they feel, but also hinder productivity, increase mistakes and raise physical safety risks.

Psychosocial risks are linked to mental and physical harm

Decades of research have clearly established the impact on mental health outcomes and psychological harm of psychosocial hazards at work. Workplace factors like high workloads, poor support and job insecurity can lead to negative outcomes such as anxiety, depression and burnout.

Increasingly, however, the physical harm caused by psychosocial hazards is becoming clear. This is particularly relevant for industries where physical safety is paramount, like construction, manufacturing and agriculture, as the MATES survey showed. Psychosocial hazards are workplace safety risks that demand the same urgent attention we give to physical hazards like working at height or operating machinery. Musculoskeletal disorders, especially in the back, neck and shoulders, are just one example of how psychosocial factors are linked to physical health outcomes.

Research shows that high psychosocial work demands, or chronic work-related strain without opportunities for recovery or coping, can result in stress and exhaustion for workers from the office to the building site and, in the long term, increase the risk of chronic illness. We also see high workloads, low job control, poor support and bullying increase the risk of musculoskeletal disorders.

The stress pathway to physical harm

Understanding how psychosocial hazards translate into physical harm helps us better manage them. The pathway typically follows this pattern:

Psychosocial Hazard → Stress Response → Physical Consequences

For traditional safety risks, the cause-and-effect is usually quite clear: poor ergonomics can cause back pain; working at height can lead to falls.

Psychosocial hazards operate slightly differently. When we’re exposed to psychosocial hazards such as excessive workload, job insecurity or workplace conflict, our brains detect a threat, which activates the sympathetic nervous system, triggering the “flight-or-fight” response. Stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol flood the body, raising heart rate, blood pressure and glucose levels to prepare our bodies for action.

In the short term, this physiological response can help us cope with demanding tasks or give us the courage to speak up. But when stress responses are chronically activated, the effects are harmful. Sleepless nights as we worry about trying to keep up; anger spilling out onto loved ones as we feel helpless to deal with or change anything at work; tense muscles every time the boss walks by; eating too little, drinking too much, dreading work day after day … This has a “wear-and-tear” effect on the body, often described through the “allostatic load framework”, which shows how repeated stress gradually weakens multiple physiological systems. We might experience increased inflammation, cardiovascular disease, weakened immunity and other serious health conditions.

When psychosocial and physical hazards interact

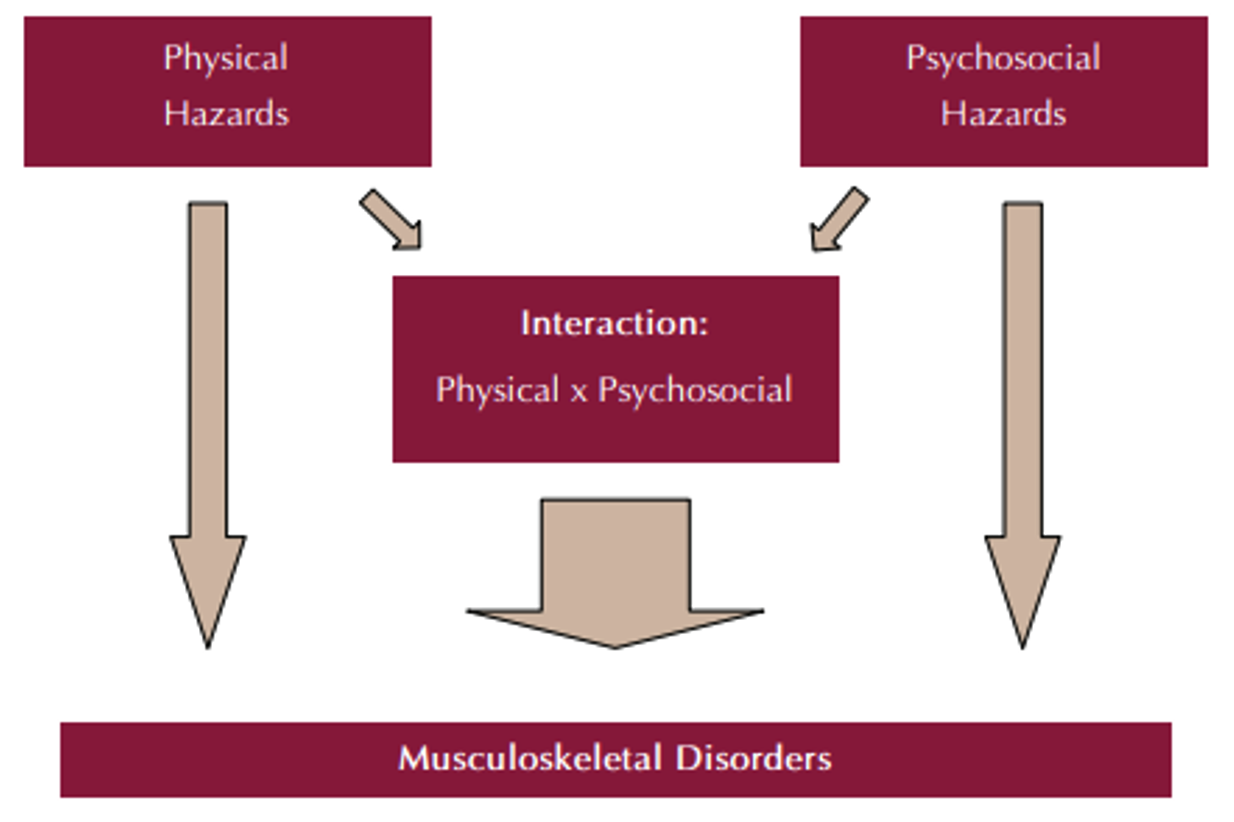

Researchers also suggest that physical hazards and psychosocial hazards can interact and amplify the risk of harm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Musculoskeletal disorders caused by physical and psychosocial hazards

Source: WHO Health Impacts of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview; Adapted from Leka et al., 2008.

For example, a study of more than 600 manual workers, delivery drivers, customer service operators and office staff found that people exposed to both high physical demands and high psychosocial risks had the highest increase in risk of musculoskeletal problems (hand, wrist, and upper limb disorders). Those exposed to only one type of risk, either high physical or high psychosocial, had elevated risk, but not as severe.

Practical steps to manage psychosocial risk and physical safety

Recognising that psychosocial hazards can cause physical harm changes how we approach risk management. Here are practical steps your organisation can take:

- Expand your risk assessment lens

Don’t treat psychosocial and physical risks as separate issues. When conducting risk assessments, consider questions such as “How are psychosocial risks integrated into our existing health and safety governance structures?”, “Are risk assessments capturing both physical hazards and the psychosocial/organisational factors?” and “Do our reporting and monitoring processes allow us to see how psychosocial risks may be influencing physical safety outcomes?”

- Implement holistic controls

Traditional safety controls focus on physical hazards, but effective controls should address the whole person, system and environment. For example, ensuring policies and procedures integrate controls for both psychosocial and physical risks (e.g., reasonable work hours and fatigue management), improving job design (e.g., balancing demands with resources by clarifying job expectations, autonomy, support etc), and developing organisational culture through psychological safety, so employees feel comfortable to raise safety concerns and suggest improvements.

- Monitor lag and lead indicators

Track both retrospective (lag) and prospective (lead) metrics to identify how psychosocial risks may be impacting on safety and wellbeing. For example, analysing workforce patterns (e.g., absenteeism, sick leave, turnover trends, or EAP usage data), monitoring safety behaviours (e.g., near-miss reports and incident trends), and drawing on wellbeing data (e.g., employee feedback, wellbeing and engagement surveys, psychosocial risk assessments) are all very useful sources of data to spot pressures before they escalate.

- Integrate support systems

Rather than treating physical and psychological support as separate services, create integrated approaches. This may involve early-intervention programmes that address both psychological and physical symptoms, return-to-work programmes that consider the whole person and psychosocial factors of work, and health and wellbeing initiatives that span both physical and mental health.

- Train leaders to recognise the signs

Equip managers and supervisors to spot when psychosocial hazards might be creating physical safety risks. This involves training and workshops to upskill leaders to be able to identify changes in work performance or behaviour, increased mistakes or near-misses, signs of fatigue or stress that could impair physical capabilities and reduced engagement with safety procedures. Importantly, leaders need to understand channels and resources available to support employees before risks escalate.

When we address psychosocial hazards by adopting a preventative approach, we’re not just protecting mental health but we’re preventing physical injuries, reducing workers’ compensation claims, and creating safer, more productive workplaces.

Want to explore how your organisation can better integrate psychosocial and physical risk management? Our team combines expertise in workplace mental health, rehabilitation, and return-to-work programmes to help you develop comprehensive approaches to workplace wellbeing. Learn more about our services.