Insights from behavioural economics and behavioural psychology

Any organisational intervention requires individual behaviour change. If you want employees to be more active, more engaged, show flexibility during change, or to use a new operating system, you are asking them to make changes to how they do things; that is, to change their behaviour.

Behaviour change involves putting new skills and habits into practice everyday. Practice creates new experiences, and new experiences create new neural pathways, which help to make the habits “stick”.

There is growing evidence that individual behavioural change is most likely to be successful when the organisational context facilitates and supports individual efforts to change. The work environment and leadership practices can help or hinder these efforts; even when organisational strategies and policies are designed to be supportive.

Information from neuroscience about the workings behind behaviour change explains why this is so. Essentially, well-established (old) behaviours or habits are like well-worn, fast-track highways in our brains. We travel down them and back home again without noticing how we got there. Setting up and maintaining new behaviours (habits), on the other hand, is a bit like bush-bashing a new track through thick scrub. The smooth highway is much easier and more appealing to travel on, compared to the hard work of the track.

However, the environment we are in can make this new track smoother more quickly. Given how many hours employees spend at work, creating an effective environment for behaviour change is helpful for both individuals and for the organisation.

Behavioural economics is the study of how people make decisions or choices and therefore what might “nudge” them to make the best ones. Behavioural psychology focuses on what are the most effective ways to help people change their behaviours. Insights from both these fields of study provide some clear guidance about how the organisational environment and leadership practices can be set up to ensure that individual behaviour change is effective.

- The surrounding structures must be in tune with the desired behaviour. If you want employees to be more physically active, there need to be spaces where they can stand to work and you need to ensure that taking activity breaks is encouraged and rewarded.

- People need to see people they respect actively modelling the desired behaviours. “Actively” means consistently, regularly and in a way that can be observed by others. Leaders will ideally be doing the modelling but other “champions” can be powerful models also.

- It’s best to focus energy and attention on establishing new behaviours and habits rather than trying to fix old ones that don’t work. Set up structures and rewards for the behaviours you do want. This is the thinking behind agreeing time limits on sending emails and why some organisations have set up IT systems to block email access at certain times. If you can’t establish a new behaviour, we’ll do it for you!

- Repetition is key. Identify which environmental prompts and leadership “nudges” will help people to practice the behaviours you want, and to practice them often. Daily is better than weekly, weekly is better than monthly. Noticing, rewarding and celebrating both extraordinary effort and small successes are examples where frequent repetition is helpful.

- Reminders and prompts to practice are also powerful. Find out from your teams which ones are most effective. Electronic? Visual? In team meetings? A variety?

- Ask people what their motivators are for behaviour change. Much of the behavioural economics research has found that motivators are not what we expect—but getting the right motivators will strongly enhance behaviour change.

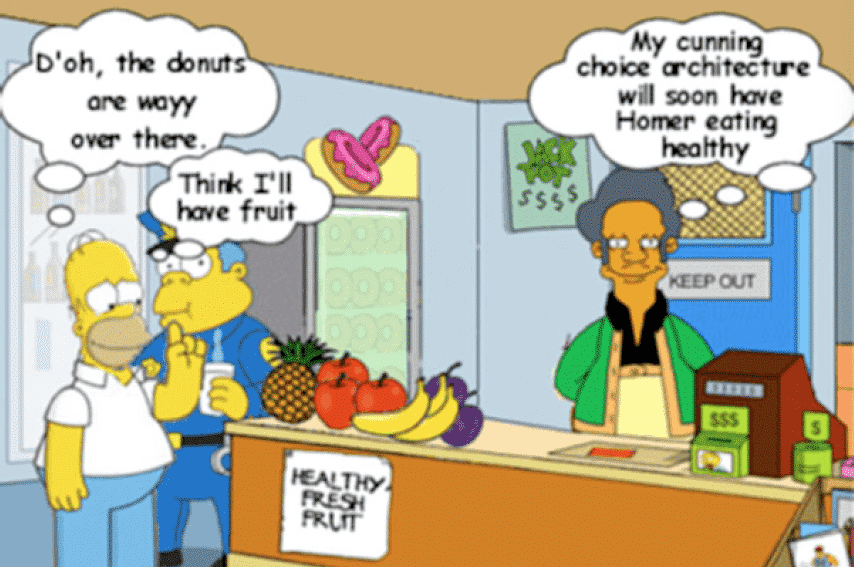

You may also want to consider the principle of “choice architecture”, where you set up the environment to support the behaviours and choices you want people to make. This works for most people.